Old Hollywood and Moving Forward

Reflections on Growth for Spring 2025

Submissions are now open for the Spring 2025 issue of The Branches Journal on the theme GROWTH. Accepting essay, poetry, fiction, art, and more with a deadline of March 15. Learn more at the button below, and read on for some of our editor’s own preliminary reflections on the theme.

How do we grow in a world that feels like it’s moving backward?

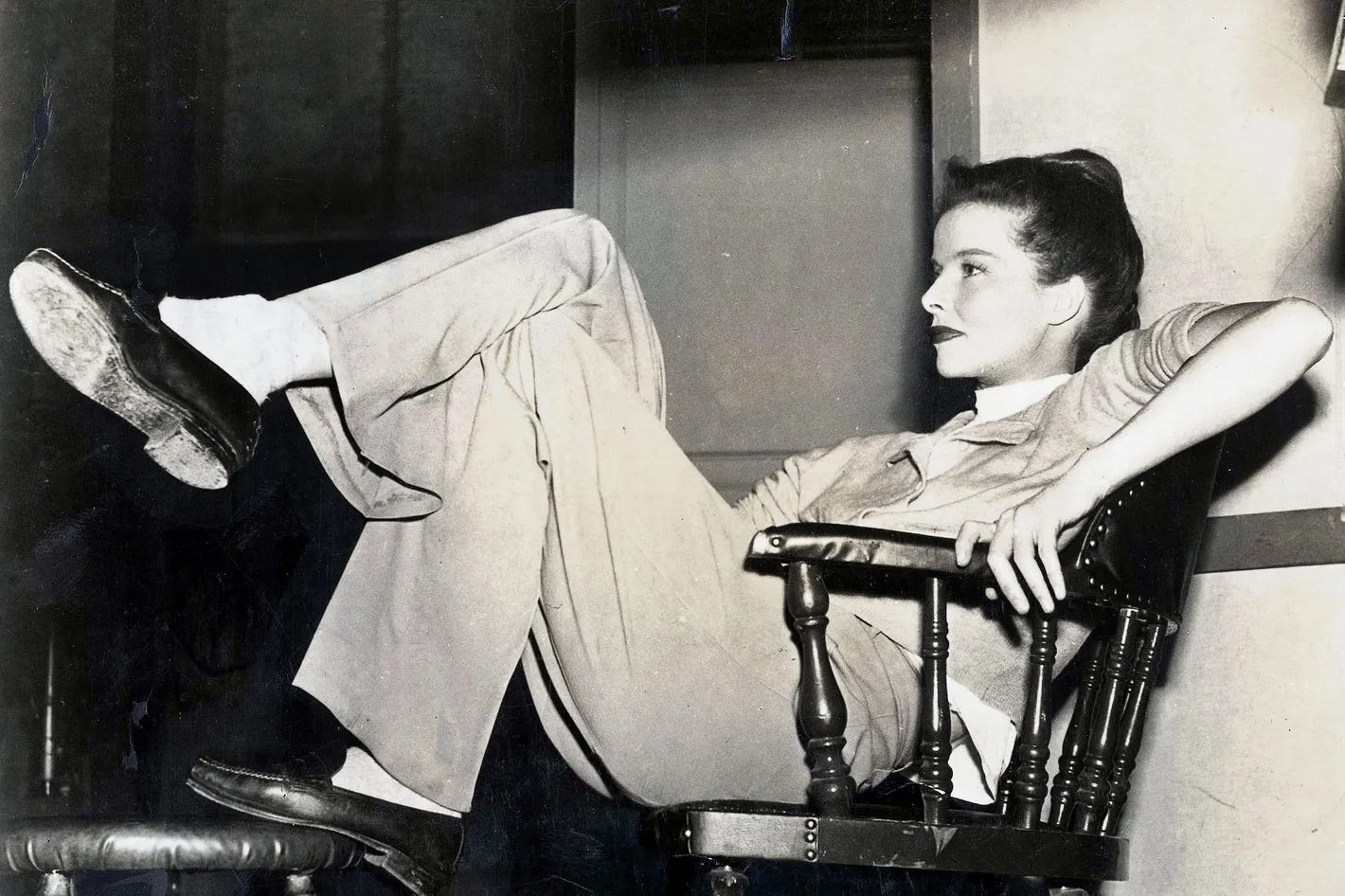

I’ve been watching a lot of old movies lately. This started at Christmas when I was visiting with family and we decided that Katharine Hepburn was a solid crowd pleaser with whom to embark on a marathon in the lazy week before New Year’s. Since, I’ve been through most of her filmography, with a good dose of Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn mixed in.

I have a lot of love for the women of Old Hollywood. I enjoy when they’re catty and manipulative in the ripple of gorgeous skirts and sharply painted lipstick. I sorrow for their limited choices and see when they’re playing along out of self-preservation or ingrained bias. I like when they talk fast. I like when they dance. I like that the answer to “Who wears the pants?” is always, always Katharine Hepburn.

Over and over, I’m surprised when these movies are surprisingly feminist in their depiction of women. This is not to say they overcome the patriarchal society of the 1930s to 1960s. Sexist plot beats and racist or misogynist jokes get thrown around, and it’s always frustrating when Audrey Hepburn has to kiss a man three times her age. But the films are often feminist in that the women are real. They can be whiney or angry; they can be sharp-tongued and pay for it; they can know what they want and be underhanded to get it, whether it’s a man or a job. They can be a ditz and the most insightful person in the room (usually both when they’re Marilyn Monroe). And they can be downright horrible: maniacal Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard, scheming Eve Harrington in All About Eve, and murderous Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity. They’re often pretty active and self-actualized even within the confines of their limiting society because they need to be rounded characters to wind up the story and make it go.

They’re not just “likeable.” They’re not just “strong.” And they’re not just “good.”

This commentary all reminds me of Kate Chopin’s late-nineteenth-century novel The Awakening, which criticizes traditional gender roles that render women submissive. The main character is a newcomer to the French Creole culture of southern Louisiana and is shocked and discomfited by the contrast between the rigid, traditional family dynamics and the casual social settings. Married women could be relaxed and straightforward, even flirtatious, because there was no possibility of actually breaching the cultural mores of marital fidelity. The presence of universal moral boundaries paradoxically allowed for greater freedom of expression.

Of course, this was no true balance. Permission to be a little less proper doesn’t stack up against the requirement to get married by twenty-five and start birthing children while the men in your life (who live under entirely different judgments) neglect you. I also acknowledge that this era was enabled by colonization and systemic racial and socioeconomic segregation. But it does contrast with the contemporary cultural moment, where a lack of universal morality causes wild swings of panic, such as the requirement for black-and-white virtue signaling from the liberal end of the spectrum while the conservative end descends into full fascism and “rad trad” cries for a regression to good old days that never existed. This latter side is much more frightening because it refuses even the social flexibility described in The Awakening’s culture. When people and realities conflict with the calcified worldview of the radical right wing, their main solution is erasure, like a child pretending he can’t see what he doesn’t like. The existence of trans people is denied; the presence of immigrants is revoked; the dignity of women is remolded until it becomes indiscernible.

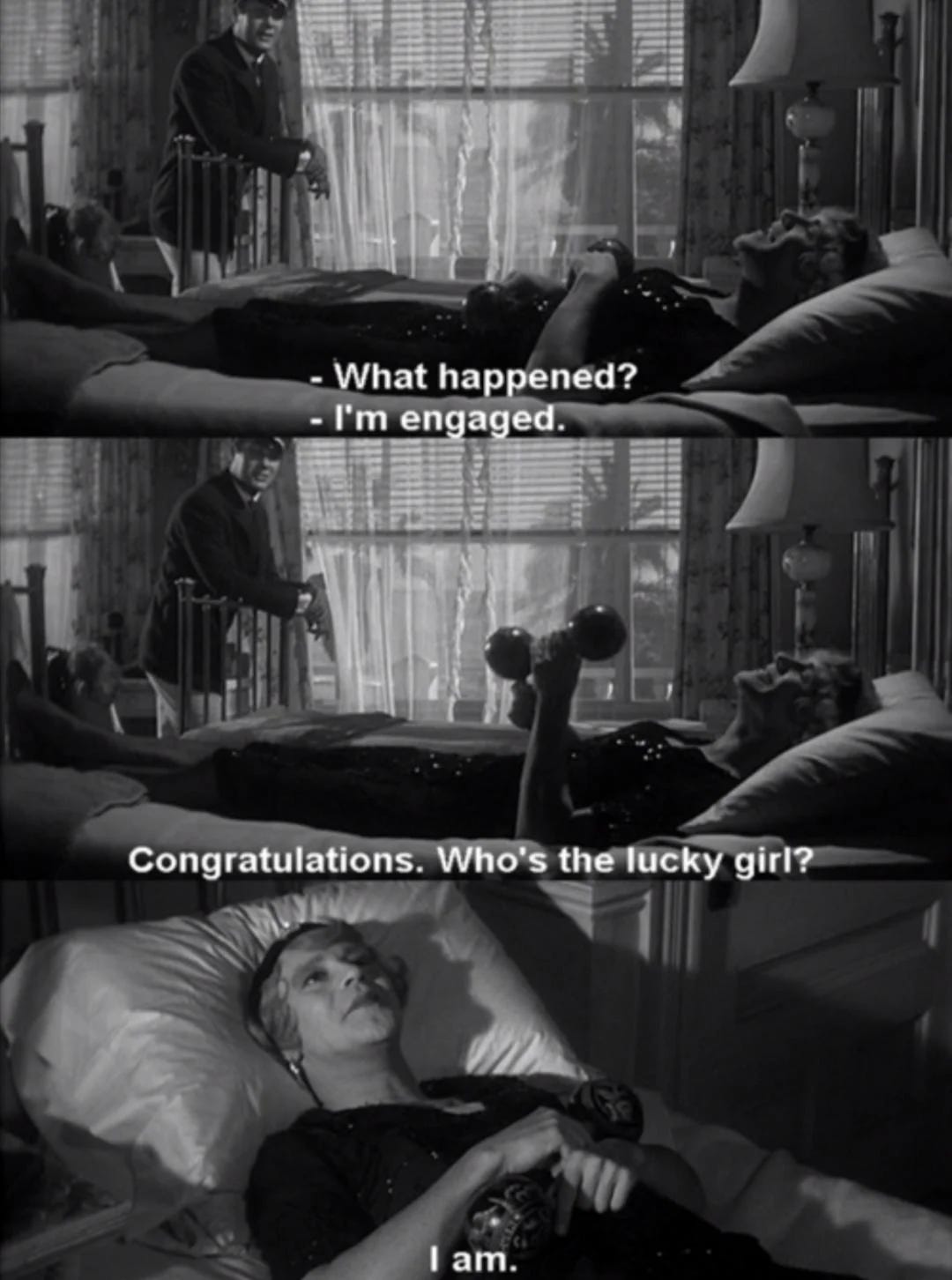

It is another paradox that the era of Old Hollywood I’ve been watching, which was regulated by the Hays Code, nevertheless wove in stories and characters that can be read as progressive. I recently saw Some Like It Hot, a farce about two men who are on the run from the mob and so dress up like women to escape to Florida with an all-female band. But it’s halfway between a joke and genuine gender euphoria when one of them starts to love spending time as a girl, picking out a new name for himself (Daphne), making Manhattans with bandmates, and dancing into the night on a date with a divorcé named Osgood.

“I’m engaged!”

“Congratulations. Who’s the lucky girl?”

“I am!”

(The other spends most of his time pretending to be a millionaire to win over Marilyn Monroe, but she gets to decide a fair bit of the budding relationship too.) And in the great closing lines of the movie, as the four escape again from the mob on a boat, Daphne confesses:

“Oh you don’t understand, Osgood. I’m a man!”

“Well, nobody’s perfect.”

The film, while definitely being a product of 1959 that likes ogling Monroe in evening gowns and has a number of off-putting gags, ends up being surprisingly queer-friendly. I can’t help but wonder what it means that Hays Code Hollywood allowed such a movie when today I can only imagine it would be met with an outpouring of outrage.

I find the following passage from one of C. S. Lewis’s essays on writing fiction relevant to this problem of contemporary discourse:

“The public has a distrust for moral books which is not wholly mistaken. Morality has spoiled literature often enough: we all remember what happened to some nineteenth-century novels. The truth is, it is very bad to reach the stage of thinking deeply and frequently about duty unless you are prepared to go a stage further. The Law, as St. Paul first clearly explained, only takes you to the school gates. Morality exists to be transcended.” (emphasis added)

We can’t transcend morality in the way Lewis describes because we’re too busy performing correctness, and indeed a correctness which is deeply biased and variable from person to person based on their predetermined opinions. The trumped-up entrenchment of the culture wars leaves us hyperfixated on writing “moral books,” whether that be Reddit posts blackballing some celebrity for a clumsy statement on a contentious issue or the literal president of the United States spewing out executive orders about people he hates. (Again, the latter is obviously more damaging for the unempathetic wielding of unchecked power.) These moral books allow no flexibility for the messy, multifaceted characters I’ve been watching and that exist in real life.

Permit me one more film description from my recent viewing. The 1937 film Stage Door features a group of aspiring theater actresses living together in a boarding house. Watching it, I nearly cried at these women, who spend their time falling over each other lounging in the common space, trading verbal barbs, lamenting lost auditions and the quality of the food, and draping a fluffy cat over their shoulders like a feather boa. They’re loud and judgmental and clever and lovelorn and depressed and bitter and hopeful, and they know what they want and haven’t got a clue what they’re doing. They stand up for what’s right and pull a couple of schemes to get what’s right to win out. They’re working on growing: developing their craft and pursuing their lives.

A few weeks ago, we had our kickoff event for the Spring 2025 issue of the journal (Growth! Submit now! Deadline March 15!), and we got into a discussion of how we motivate growth. Are we always growing against something? Can we escape from the habit of glorifying trauma as a learning experience that makes you stronger if it doesn’t kill you? One of the attendees pointed out the type of growth that comes from working on a hobby or a craft, which we do not for the sake of being measured or watching an arbitrary number go up, but for the joy and personal satisfaction it brings. She wondered, what if we apply that thought to our very selves, working on our own consciences and betterment as the craft of our lives?

That’s what the women in Stage Door are doing as they carve out careers and friendships and self-knowledge. And it’s what I hope to be doing too. But it feels so difficult to fight for personal growth in a time where it feels like culturally and collectively we are slipping and being driven backward, and not even to the surprising spunk and complexity of Old Hollywood women but to an invented past that is all regression for its own sake. What if we’re just like birds flying against the wind, working hard but getting nowhere? Will there be any winner in the culture wars, or will we be left with demanding posttraumatic growth from ourselves in the aftermath?

I’m left with more questions than answers, but that may be the point. We selected the theme of Growth for this upcoming issue as a way to build on the previous theme of Purpose. Once you deliberate on what your purpose is, you have to go somewhere with it—you have to grow—even if that brings you up against conflict and confusion. I hope to keep pressing on during this cycle of The Branches Journal, and we look forward to reading your submissions!

Elizabeth Coletti is an editor, writer, and museumgoer from North Carolina now living in New York.

Local to NYC? Join us at our next meetup event at Culture Lab LIC on February 23.